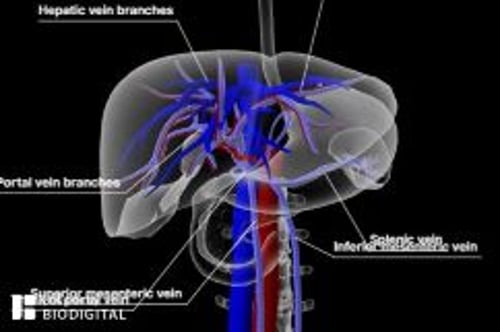

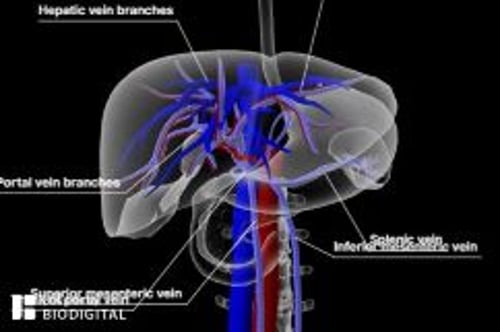

Budd-Chiari syndrome is obstruction of hepatic venous outflow that originates anywhere from the small hepatic veins inside the liver to the inferior vena cava and right atrium. Manifestations range from no symptoms to fulminant liver failure. If suspected, initial testing is Doppler ultrasonography. Treatment includes supportive medical therapy and measures to establish and maintain venous patency, such as thrombolysis, decompression with shunts, and long-term anticoagulation.

In the Western world, the most common cause is a clot obstructing the hepatic veins and the adjacent inferior vena cava. Clots commonly result from the following:

Sometimes Budd-Chiari syndrome begins during pregnancy and unmasks a previously asymptomatic hypercoagulability disorder.

The cause of obstruction is often unknown. In Asia and South Africa, the basic defect is often a membranous obstruction (webs) of the inferior vena cava above the liver, likely representing recanalization of a prior thrombus in adults or a developmental flaw (eg, venous stenosis) in children. This type of obstruction is called obliterative hepatocavopathy.

Budd-Chiari syndrome usually develops over weeks or months. When it does develop over a period of time, cirrhosis and portal hypertension tend to develop ( 1 ).

Manifestations range from none (asymptomatic) to fulminant liver failure or cirrhosis . Symptoms vary depending on whether the obstruction occurs acutely or over time.

Acute obstruction causes fatigue, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, mild jaundice, tender hepatomegaly, and ascites. It typically occurs during pregnancy. Fulminant liver failure with encephalopathy is rare. Aminotransferase levels are quite high.

Chronic outflow obstruction (developing over months) may cause few or no symptoms until it progresses, or it may cause fatigue, abdominal pain, and hepatomegaly. Lower-extremity edema and ascites may result from venous obstruction, even in the absence of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis may develop as well as manifestations of portal hypertension , including variceal bleeding , massive ascites, splenomegaly, hepatopulmonary syndrome , or a combination. Complete obstruction of the inferior vena cava causes edema of the abdominal wall and legs plus visibly tortuous superficial abdominal veins from the pelvis to the costal margin.

Budd-Chiari syndrome is suspected in patients with hepatomegaly, ascites, liver failure, or cirrhosis when there is no obvious cause (eg, alcohol abuse, hepatitis) or when the cause is unexplained.

Liver tests are usually abnormal; the pattern is variable and nonspecific. The presence of risk factors for thrombosis increases the consideration of this diagnosis.

Imaging usually begins with abdominal Doppler ultrasonography, which can show the direction of blood flow and the site of obstruction. Magnetic resonance angiography and CT are useful if ultrasonography is not diagnostic. Conventional angiography (venography with pressure measurements and arteriography) is necessary if therapeutic or surgical intervention is planned.

Liver biopsy is done occasionally to diagnose the acute stages and determine whether cirrhosis has developed.

Treatment varies according to onset (acute vs chronic) and severity ( fulminant liver failure vs decompensated cirrhosis or stable/asymptomatic). The cornerstones of management are

Aggressive interventions (eg, thrombolysis, stents) are used when the disease is acute (eg, within 4 weeks and in the absence of cirrhosis). Thrombolysis can dissolve acute clots, allowing recanalization and so relieving hepatic congestion. Radiologic procedures, such as angioplasty, stenting, and/or portosytemic shunts, can have a major role.

For caval webs or hepatic venous stenosis, decompression via percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty with intraluminal stents can maintain hepatic outflow. When dilation of a hepatic outflow narrowing is not technically feasible, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) and various surgical shunts can provide decompression by diverting blood flow into the systemic circulation ( 1 ). Portosystemic shunts are typically not used if hepatic encephalopathy is present; such shunts may worsen liver function. Further, clots may form in shunts, especially if patients have a hematologic or thrombotic disorder.

Long-term anticoagulation is often necessary to prevent recurrence. Liver transplantation may be lifesaving in patients with fulminant disease or decompensated cirrhosis.

Without treatment, most patients with complete venous obstruction die of liver failure within 3 to 5 years. For patients with incomplete obstruction, the course varies.